They also underwent f unctional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity while they performed various decision-making tasks. Unlike the Lumosity programs, these games were specially designed not to tax the brain’s executive function or to increase in difficulty.Īt the start and the end of the study, all participants took a battery of standard cognitive tests. The second group was similarly instructed, but they were given computer games to play. One group was told to use the Lumosity programs five times a week, 30 minutes a day for 10 weeks. The participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups.

LUMOSITY BRAIN GAMES TRIAL

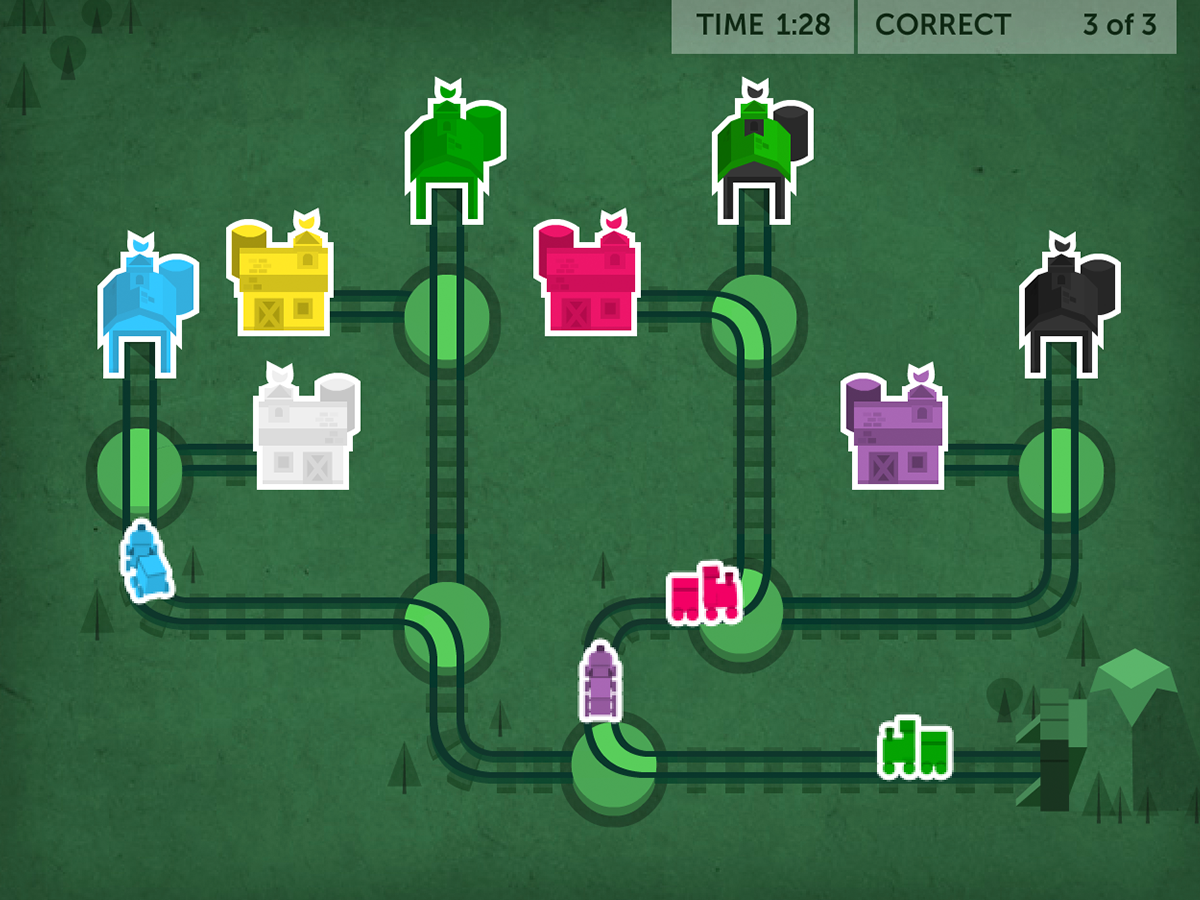

They thought such programs might help individuals reduce the tendency to make risky or impulsive choices - and therefore might be a useful intervention for reducing unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking or overeating.įor the study - a randomized controlled trial - they recruited 128 healthy, young men and women between the ages of 18 and 35. The University of Pennsylvania researchers began the current study, however, believing they would see a benefit from brain-training programs. In 2016, Lumos Labs, the marketer of the Lumosity games, paid $2 million to the Federal Trade Commission for misleading the public - particularly the elderly - with unsubstantiated suggestions that its products could help protect against memory loss and even dementia.Īnd earlier this year, a randomized controlled study - considered the gold standard of research - reported that computer brain-training programs did not provide any kind of cognitive “boost” to older people. This study’s findings are more bad news for the billion-dollar computer brain-training industry. They found that Lumosity’s programs did not make people’s brains work any more efficiently or effectively - beyond improving their skills at doing the programs themselves. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania pitted the popular Lumosity brain-training games against a set of computer games designed only for fun. Brain-training computer programs are no better at improving people’s ability to make decisions, remember or concentrate than computer games whose purpose is simply to entertain, according to a study published Monday in the Journal of Neuroscience.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)